Healthy soils have a degree of resilience that allows them to maintain their structure and function in the face of repeated disturbances.8.9, including temperature disturbance10, compactioneleven and copper contamination12. Provide essential ecosystem services3 such as food production and can help us achieve several Sustainable Development Goals, including zero hunger, clean water and sanitation, life on earth, flood regulation, and biodiversity conservation13. However, human-induced degradation, such as soil erosion, pollution, and loss of soil organic carbon (Fig. 1), is compromising soil resilience.3.14. Population growth, unsustainable agricultural practices, deforestation, industrial development, urbanization and, increasingly, climate change pose the greatest threats to healthy soils.3.14.15. Once disturbed beyond a critical level, soils risk entering a downward spiral into an alternate, degraded state.9.14. This degraded state is characterized by the loss of soil functions and services, including the ability to provide food for humanity and sustain human life on Earth.14.16. Since soil restoration is a slow process, soil is often considered a non-renewable resource.6,9,14,15.

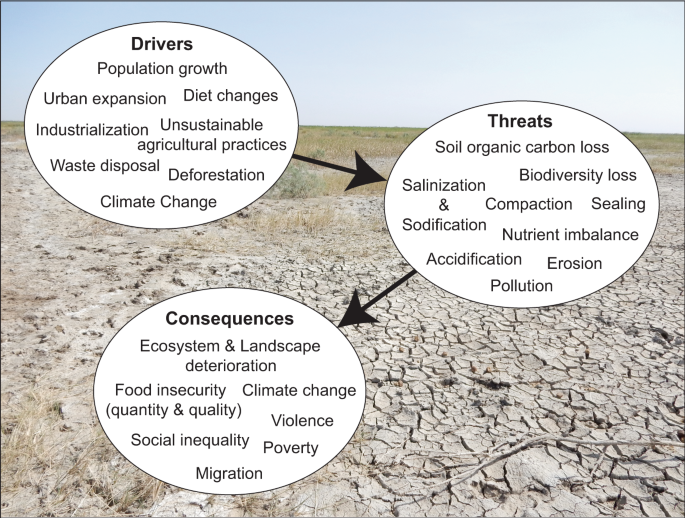

The soil degradation process described by the main drivers, quantifiable threats and consequences of soil degradation on planetary and social health.

The downward spiral of soil degradation is driven by soil threats that are strongly interrelated and linked through powerful feedback loops. On a local scale, loss of soil structure due to compaction by heavy machinery or intensive grazing results in loss of soil biota and soil functioning and further degradation.17. On a global scale, there is a strong positive feedback loop between soil erosion and climate change. Soil erosion causes a loss of soil organic carbon in the form of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere, which contributes to global warming.14. Warmer conditions lead to increases in rainfall intensity, wind speeds, and forest fires, all of which can increase soil erosion.14.18.

A degraded soil condition is not uncommon in human history. The fall of past civilizations has been related to the poor protection of soil health by societies.19. Among these, the Sumerian civilization in Mesopotamia was undermined by salinization and highland erosion.19, while both Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire suffered from severe and widespread soil erosion19. Where healthy soils initially allow civilizations to grow and prosper, increased demand for food production and unsustainable agricultural practices result in severe soil degradation. Followed by a decline in food security and political stability, land degradation compromises the resilience of civilizations and begins their collapse.19. In the past, however, the human population was smaller, more dispersed, and less connected than it is today.6. This means that past impacts of land degradation only undermined local ecosystems and societies. Today, with a human population of 7.9 billion people expected to grow to 9.8 billion by 2050 and a strongly globalized world, land degradation is no longer a local problem.6. Land degradation is already negatively affecting the well-being of at least 3.2 billion people around the world.twenty by decreasing food security and landscape resilience to extreme weather events, resulting in increased inequality and political instability15.20. In the European Union alone, costs related to soil degradation exceed 50 billion euros per yearfifteen. On a global scale, land degradation has also been linked to mass migration, violence and armed conflict.19.20. Soil degradation is estimated to affect 90% of soils globally by 20503, which means that almost all the world’s ecosystems and populations will be directly affected.