Newswise – December 15, 2021 – Today’s modern economy generates a lot of waste. Waste that accumulates in landfills, bodies of water and city streets. In countries that can afford sewage systems, human excreta is generally treated in a sanitary manner. But for poorer countries, human waste disposal, especially in cities, can cause health problems.

Another thing about human waste is that it has enormous potential value that can be harnessed if we don’t waste it. Urine has most of the nitrogen and phosphorus, both key ingredients in fertilizers, in our diets. Stool contains organic matter and nutrients. Both by-products of human ingestion can be reused, if properly treated.

Not recycling post-consumer nutrients is bad for your health, the environment, and the economy. Greenhouse gases released when excreta are dumped in landfills contribute to climate change. It is truly a waste not to reuse our – waste.

Rebecca Nelson of Cornell University presented a new vision for human waste reuse at the 2021 Annual Meeting of the ASA, CSSA and SSSA. The title of Nelson’s talk, which is part of Betty Klepper’s lecture series, was “The Soil Factory Network: Towards the circular economy of bionutrients ”. The meeting was held in Salt Lake City, November 7-10, 2021.

“I am a plant pathologist,” says Nelson. “But I’ve really come to realize that plant health requires soil health. That led me to focus on a circular economy for organic nutrients, including nutrients from food waste, before and after human consumption. “

“Climate change causes many problems, including floods and droughts. In many parts of the world, soils are depleted of nutrients and organic matter. Poor soil stresses plants, reducing yields and making crops more prone to disease. “

From a one-way nutrient system to a circular economy

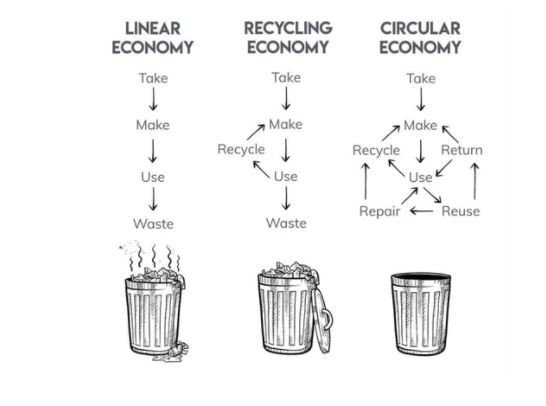

Farmers with adequate resources can apply fertilizers to maintain crop yields. But beyond the cost of buying and applying the fertilizer, there are energy costs to produce the fertilizer, transport it to suppliers, and then to the farm. And, once used, it is a one-way system, which is a waste.

Resource-limited farmers in many parts of the world have difficulty accessing conventional fertilizers. They also tend to have poorer soils that do not respond well to nutrients because their soils lack organic matter. A study from the University of Illinois showed that, in many parts of the world, urine sources are close to agricultural production. Using the concept of circular economy of nutrients and reusing this urine would help farmers and create a more sustainable food system.

“We have a chance,” says Nelson. “We can recognize human excreta not only as a problem, but also as a resource and an opportunity to reduce greenhouse gases. Ecological sanitation [as part of a circular nutrient economy] it’s an excellent option. “

Liquid gold

Urine is rich in nitrogen and phosphorus. Nutrients in an adult’s urine can be used to grow 320 pounds of wheat, according to the Rich Earth Institute. In addition, they note that each person typically flushes 4,000 gallons of drinking water each year.

“Much of the United States is suffering from extreme drought, so the time is right to look for an alternative. [to our wastewater systems]”Says Nelson. “The urine diversion makes a lot of sense. Most of the nutrient contamination in wastewater comes from urine, although it is a small fraction of the total volume. If we capture it at the source, we can recover the nutrients much more easily than if we dilute it with running water and contaminate it with excrement and industrial toxins ”.

“In countries with fewer resources,” Nelson says, “container-based sanitation is even more attractive because 2.4 billion people have no sanitation and the need for fertilizers is even more urgent. This new recycling and waste management industry creates job opportunities and reduces water pollution. “

Solid waste

Human solid waste can be safely processed in a number of ways. Faeces are a source of organic matter that can improve soil texture and its ability to absorb rainwater, mitigating the effects of drought on crop production.

Wastewater treatment plants convert solid waste into “biosolids”, which are regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency. Solid waste, whether biosolids or faeces separated at source, can also be converted to biochar. This can also be added to the soil as a carbon source.

Waste reuse in action

Some cities in the US have started to use biosolids from their wastewater systems. Tacoma, Washington, sells its biosolids under the name Tagro. Chicago, Illinois, is using biosolids in its urban remediation projects. The Rich Earth Institute in Vermont has a community urine cycling program and has published a guide titled “Guide to Starting a Community Scale Urine Diversion Program.”

Internationally, several organizations run container-based sanitation systems. For example, SOIL provides containerized sanitation to 6,500 people in Haiti, and Sanergy serves 125,000 people in Kenya. Both companies produce compost that is used to grow higher-yielding food.

“There are a variety of companies that make source separation toilets,” says Nelson. “The Swedish toilet company Separett makes a variety of models, for example, and there are other suppliers and models for every budget and context.”

“There is a great opportunity to solve a number of problems, from water pollution to food insecurity to poor sanitation, by recycling nutrients in human excreta,” says Nelson. “We need to rethink current decoupled food production and waste management systems. Especially in poorer countries with less access to fertilizers, safe reuse of urine and faeces has been shown to increase agricultural productivity. The great challenge is to develop complete value chains that serve a large number of people and close the nutrient loop through the production of fertilizers, insects for animal feed and energy ”.

Funding for this project was provided by: The McKnight Foundation; Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability; Cornell Office of Engagement Initiatives; Tata Cornell Institute.

.