Sixty years after her trailblazing chimpanzee research revolutionized the science of animal intelligence, Jane Goodall is a living legend — and not the least bit comfortable with her still-growing fame.

“I’ve become this kind of icon,” says the 87-year-old Goodall, her voice halting, as discomfort trumps her usual eloquence. “I didn’t plan it. It still surprises me. I mean, OK, young lady and chimps, I can understand that. But what’s happening to me now is a mystery.”

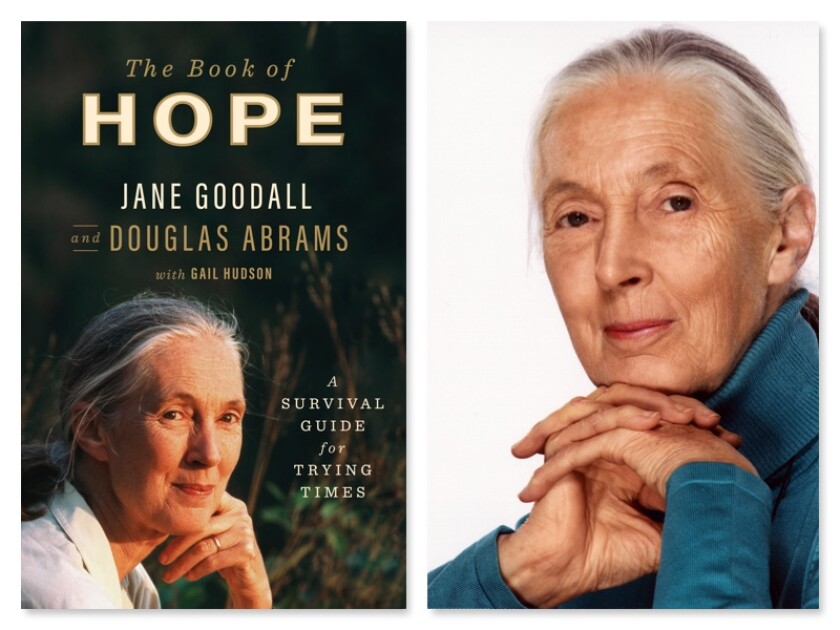

Goodall, a prolific author and scientist, will join the Los Angeles Times Book Club on Feb. 25 for a virtual conversation about her career and latest project, “The Book of Hope: A Survival Guide for Trying Times.” She’s also the subject of the current “Becoming Jane” exhibit at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

Since the pandemic began, Goodall has been staying at her family home in the south of England, far from the forest in Tanzania where her Jane Goodall Institute continues research on chimps and conservation.

In March Goodall is hoping to finally see the Los Angeles exhibit, provided that she and her team of advisors decide a US trip is safe for someone whose age makes her more vulnerable to COVID-19. “They seem very anxious about my health,” she says.

Inside “Becoming Jane: The Evolution of Dr. Jane Goodall” at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. It runs through April 17.

(Elon Schoenholz/Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County)

The pandemic forced Goodall to curtail her practice of traveling 300 days a year to give lectures around the world. Instead, she found herself sequestered in a Gothic-style house, built in 1872, with her sister Judy, other family members and an aging rescue whippet named Bean.

“I was frustrated and angry,” she concedes. But, she came to realize, “That wasn’t going to help anybody.”

With the assistance of a tech consultant and her institute staff, Goodall shifted to online speaking engagements — and found that she could do even more events. “It’s actually much more exhausting than being on the road, because there’s no gaps now,” she says. “Even on Christmas, I had a couple of Zooms. But the plus side is that I can reach millions more people, in many more countries.”

Additionally, she says, “It’s better for the environment if we don’t always travel all the time.” Even so, she worries about the effect that curtailing tourism will have on African national parks, which struggle to pay for the rangers needed to protect wildlife.

Goodall and co-author Douglas Abrams began working on “The Book of Hope” before the pandemic. As she notes in the introduction, she envisioned providing “solace in a time of anguish, direction in a time of uncertainty, courage in a time of fear” to people who, like her, found themselves disheartened by sometimes feeling that the fight for environmental and social justice is a losing battle.

(Andrew Zuckerman/Celadon Books)

The book takes the form of a series of conversations in which Goodall explains what she’s learned from her life experiences and offers four reasons for hope: the amazing human intellect; the resilience of nature; the power of young people; and the indomitable human spirit.

“It’s come out, I think, at exactly the right moment, judging from the number of letters and emails that I’ve received, saying ‘this book has really helped me at this difficult time,’” she says.

Goodall urges those disheartened by the past two years and continuing environmental decline to embrace their feelings — what she calls “eco-grief” — and use that emotional energy to combat powerlessness and despair.

“You hear this expression all the time — ‘Think globally, act locally,’” Goodall says. “But it’s the wrong way around, because if you think globally, it cannot help but be depressed, with climate change, corruption, the rise of the far right, all these things. … You think, what can I do? And so you become apathetic and do nothing.

“But if you twist it around and say, yes, but what about where I am? Is there anything here I can do?” Rescuing stray animals, growing organic food and working to help the homeless are examples of small-scale good deeds that can have an outsized impact if others join in, she says.

“The lucky thing is that when you make a difference, it makes you feel good,” she says. “And if you feel good, well, of course, you want to feel even better. So you tackle something else. It’s an upward spiral.”

Jane Goodall plays with Bahati, a 3-year-old female chimpanzee, at the Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary north of Nairobi in 1997.

(Jean-Marc Bouju/Associated Press)

Goodall has her own heroes, such as Muhammad Yunus, a Nobel Prize-winning banker who invented microlending in an effort to help impoverished people. She says Yunus ‘her work has served as a model for her institute’s current antipoverty efforts in African countries.

Goodall cites her mother, author Vanne Morris-Goodall, as her biggest hero.

“She was the one who supported me when I was 10, and everybody was laughing at me,” Goodall explains. “They were saying, ‘Jane, stop dreaming about going to Africa and living with animals. You ca n’t do something like that.’”But her mom de ella said,“’If you really want to do something like this, you’re going to have to work really hard, and take advantage of every opportunity. You don’t give up. You might find a way.’ That’s a message that I give now to people, particularly to disadvantaged communities around the world, and especially to girls, of course.”

Goodall also draws inspiration from a new generation of activists. Roots & Shoots, the youth-oriented environmental organization she founded in 1991, is active in 66 countries. “You empower them to take action, and they get to choose what they do,” she says. “You don’t dictate to them.”

She’s an admirer of 19-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg, whose harsh criticism of world leaders’ slowness in reducing carbon emissions is a contrast to Goodall’s own calm politesse. As Goodall explains in her book, there’s a role for both approaches. “If we don’t have hope that we can put the fire out, we will give up. It’s not hope or fear—or anger. We need them all.”

Goodall has come to realize that saving animals and nature means saving people as well. It’s an epiphany she first had during a flight over the shrinking forests around Gombe National Park, the site of her discoveries of her. “If you’re living in great poverty, you’re going to cut down the trees to try and make more fertile land or more food, or to get money from charcoal or timber,” she says. Improving lives, she says, “is a major goal, if you care about the environment, if you care about the future of the planet.”

She’s weary of journalists asking her what is the one most important thing for people to do to rescue the planet. “There isn’t one single thing that’s most important,” she says. “There’s one single thing that’s important to you. We’re so lucky to have all the different people with their concerns about saving animals and the environment, and so on. People take on different aspects because then they can work with passion about what they care about, knowing that other people are working on the other aspects.”

That approach is necessary because the threat to nature is “a pattern where you pull out the threads, like biodiversity, and animal and plant species become extinct,” Goodall says. That tapestry unravels and ecosystems then collapse.

Goodall says environmental destruction is one of the reasons that humans face a heightened risk from diseases such as COVID-19. “The people studying these important zoonotic diseases have been telling us for years and years that there would be a pandemic like this, and there have been many epidemics,” she says. “And they come from, yes, the destruction of the environment, which forces some animals closer to people. People are invading the forest, forcing them closer to animals. Also the trafficking of animals sending in, you know, babies to be eaten, or adults for that matter, breeding and wildlife markets around the world or to be sold as pets at wildlife markets around the world.”

Jane Goodall at the Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary north of Nairobi in 1997.

(Jean-Marc Bouju/Associated Press)

Goodall wasn’t yet focused on such daunting global issues when she began her career in the early 1960s; back then, the daunting challenge was finding a way to become a scientist. Her initial career break came after a school friend in England invited Goodall to visit a family’s farm in Kenya, and she heard about famed paleoanthropologist Louis Leakey, who had devoted his career to searching for the fossilized remains of the earliest human ancestors. Goodall met him in Nairobi, and when Leakey’s secretary suddenly quit, he hired Goodall to take her place from her.

Leakey was impressed with his 26-year-old assistant. Though Goodall had no experience in research and didn’t have a college degree, Leakey sent her in July 1960 to study chimpanzees in the forests of what is now Tanzania, in hopes that their behavior might shed light on human evolution.

Goodall struggled at first event to catch a glimpse of the chimps. The animals eventually grew comfortable enough with her presence from her to allow her to observe them; she watched a chimp she named David Greybeard use twigs and grass stems to catch termites.

Her discovery that chimpanzees used tools revolutionized how we perceive animals’ intelligence — though at first she had trouble getting the scientific establishment to take her work seriously. “The professors at Cambridge told me I’d done everything wrong, that chimpanzees shouldn’t have names, they should have numbers, and that I couldn’t talk about their personality, mind or emotion because those were unique to us,” she recalls.

Goodall has documented her work in numerous books, including a 1999 memoir, “Reason for Hope.” Last year, the Jane Goodall Institute published “#EATMEATLESS: Good for Animals, the Earth & All,” a collection of 80 plant-based recipes with a foreword by Goodall.

As she approaches 90, Goodall looks forward to new projects, including a book of stories about other people who have made an impact upon her.

“I’m trying to live up to that Jane out there,” she says. “The one I feel is separate from the one you’re talking to. You know, the ordinary human being who happens to have had amazing things happen in her life of her. Lucky me.”

Book Club: Jane Goodall

What: Jane Goodall discusses “The Book of Hope” with Times reporter dorany pineda at the LA Times Book Club.

When: 6pm PST, Feb 25.

Where: Free virtual event will stream on Twitter, Facebook and YouTube. Get tickets and signed books on Eventbrite.

Book club newsletter: Join our community book club: latimes.com/bookclub

“Becoming Jane: The Evolution of Dr. Jane Goodall” at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County.

(Elon Schoenholz/Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County

)