DSpite an investigation by BBC’s rural affairs broadcaster Tom Heap, the network continues to peddle fact-challenged study guides promoting organic farming.

Bitesize, the BBC’s free online study support resource, has long featured an explainer on “Food security—a global concern”, an important but fraught subject. It addressed different ways to increase food sustainability, a driving issue globally but particularly in the UK where future farm policy is being debated against the backdrop of the EU’s Farm to Fork Strategy. As first posted last year, WayBack Machine captures the online guide’s rhapsodic claims about organic farming:

So, according to this student resource, organic yields increase over time to equal conventional farming (which the site weirdly referred to as “inorganic farming”). Is that accurate? Is organic farming both yield intense and more sustainable?

Farmer and ‘agtivist’ RealMuckSpreader, who has a significant following on Twitter, spotted this BBC resource last fall, branding it “Shocking!“ and “Utter BS”.

Facts on organic farming and sustainability

Per-acre yields of organic crops are significantly lower than those for conventional, with estimates in the most recent meta-analysis showing a shortfall of 29-44 percent, and even higher among some grains and vegetables. These gaps have been confirmed by recent data produced by the US Department of Agriculture.

TO 2019 Nature study conducted by scientists at the Royal Agricultural University in the UK concluded that if all farms in England and Wales converted to organic production, yields would decline by half, necessitating the use of more farmland elsewhere in the world to make up the deficit. According to co-author Laurence Smith, himself an advocate of organic farming“The key message from my perspective is that you can’t really have your cake and eat it ….”

There is an emerging science consensus that GMO crops and conventional agriculture in general are more sustainable than organic agriculture when carbon emissions are factored into the equation. Agriculture plays a complex role when it comes to climate change. Farming contributes a significant share of certain greenhouse gases (nitrous oxide and methane)—as much as 10% in the US by USDA estimates—and quite a bit of CO2 is also emitted through fuel consumption and for nitrogen fertilizer production. This approach all but rules out both synthetic chemicals and modern biotechnology, including CRISPR gene editing now being embraced by almost every advanced industrial region of the world outside of the EU.

There is a widespread, misguided belief that organic/agroecological agriculture is the best option to address global warming — a belief prevalent in Europe, and reflected in a goal of 25% organic farming in the Green New Deal Farm to Fork strategy. while restricting access to GMOs and gene edited crops.

In fact, that would be a very bad idea. Organic farming is less productive in general and so its various footprints (land, water, GHG emissions…) are greater per unit of usable crop yield. Composting of manure to make it safer for use as a fertilizer can generate major greenhouse gas emissions. The limited pesticide options allowed in organic production can lead to greater fuel use for mechanical weeding or more frequent sprays of less efficacious insecticides and fungicides. (See this assessment).

Multiple impact assessments (here, here, here) have appeared in recent weeks challenging the sustainability claims of F2F supporters. They unanimously conclude that because of the yield drag and the carbon released linked to tilling practices of organic farmers (many conventional farmers utilizing GM crops use low or no till practices), carbon releases would soar, significantly damaging global efforts to control climate change disruptions.

Organic farming and chemical usage

What about the BBC’s insinuation that organic agriculture uses less toxic chemicals? That’s misleading. Organic farmers widely used chemicals, including some are more toxic than synthetic alternatives. Recent research also shows that the ‘natural’ chemicals used to support some organic crops, such as reliance on copper-based pesticides to grow wine grapes as well as tomatoes, apples and potatoes, are actually far worse for the environment and biodiversity than synthetic alternatives. used by conventional farmers.

According to the European Chemical Agency (ECHA), copper sulphate “is very toxic to aquatic life, is very toxic to aquatic life with long lasting effects, may cause cancer, may damage fertility or the unborn child, is harmful if swallowed, causes serious eye damage, may cause damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure.” The 2021 Esteban study by Public Health France of the country’s population revealed the presence of copper in almost the entire French population, and in particular in children who consume organic products.

Moreover, European countries, a global center for organic farming, use significantly more chemicals per hectare, including toxic ‘natural’ alternatives, than do farmers in the US and Canada. Netherlands (24), Belgium (28), Ireland (29), Italy (31), Portugal (36), Switzerland (41) Germany (44) and France (47)—indeed, almost every country in Europe—use far more toxic pesticides per hectare of available cropland than the United States, demonized in Europe as an agrochemical junkie. The US ranks 59th.

Since the mid-1990s insecticide use on American farms has fallen 61%-81% as the direct result of the introduction of GMO corn, soybeans and cotton engineered to express the natural bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis (bt)— also used as a spray by organic farmers—that resist or kill some 200 harmful insects.

How did the BBC respond when its misstatements were flagged?

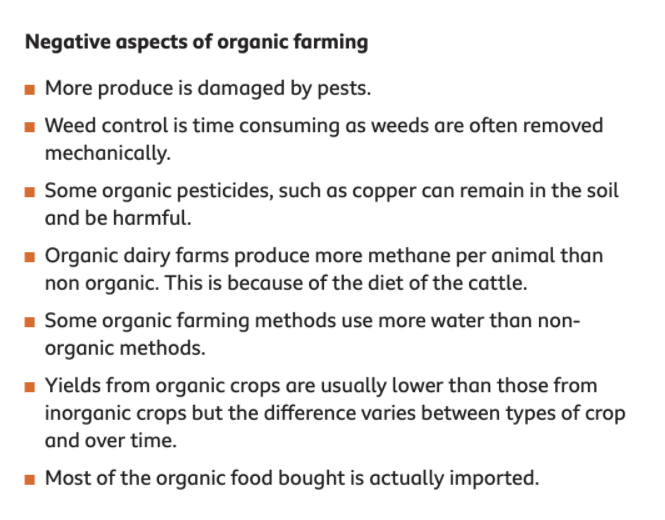

That original post and cyberspace flare up caught the attention of BBC’s Tom Heap, who knows his science. How did the BBC respond to the criticism? Misleadingly at best. Constructively, due to Heap’s intervention, in a section called “Farming and rural areas,” BBC appropriately revised misinformation glorifying organic farming. It now acknowledges that “Organic farming is less efficient and so produce does cost more” and notes a range of environmental challenges posed by organic farming:

But this rural farming section of the site is rarely visited in contrast to the pages focusing on sustainable farming, a more compelling issue and the focus of intense lobbying by pro-organic forces. The reviews in that section are far more modest, muddled and scientifically suspect. Rather than acknowledging the documented organic yield shortfall, the post now waffles and confusingly claims that the difference in yield with conventional “varies” over time.

BBC also continues to peddle the fiction that organic farming is considered ‘environmentally sustainable,’ despite overwhelming research that the yield lag, the heavy use of tilling which releases carbon from the soil, and a reliance on methane-burping cows to produce manure have turned large-scale organic agriculture into a climate change time bomb.

That the BBC continues to peddle obviously ideological and science-bereft claims underscores how entrenched pro-organic, anti-conventional agriculture mythology is rooted in the UK and Europe. It downplays or dismisses the dramatic role technology, including biotechnology, has played in increasing yields while lowering the environmental footprint of modern farming.

Many of us have warned for some time that we cannot afford to be complacent with something as fundamental as food security. The unfolding crisis in Ukraine is a brutal reminder that the global food supply and demand balance today remains as precarious as 11 years ago when Sir John Beddington’s Foresight report urged governments to embrace new technologies and pursue policies of ‘sustainable intensification’ in agriculture to meet future food needs.

Improving agriculture to address climate change and food insecurity will require every tool available. That means “natural” solutions like ‘organic only’ will not be enough, and could in some cases exacerbate problems.

Faced with the challenges of population growth, rising temperatures and finite natural resources of land, water and fossil fuels, a sustainable future for farming and food production lies in modern science and innovation, not turning back the clock to a nostalgic past that never really existed . That’s why it is so important that our young people — the next generation of consumers — are properly informed with the facts about different farming systems, not pro-organic fairy-tales and propaganda.

Let’s hope BBC gets the message.

Matt Ridley is a British journalist and businessman. He is the author of several books, including How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom. Follow him on Twitter @mattwridley